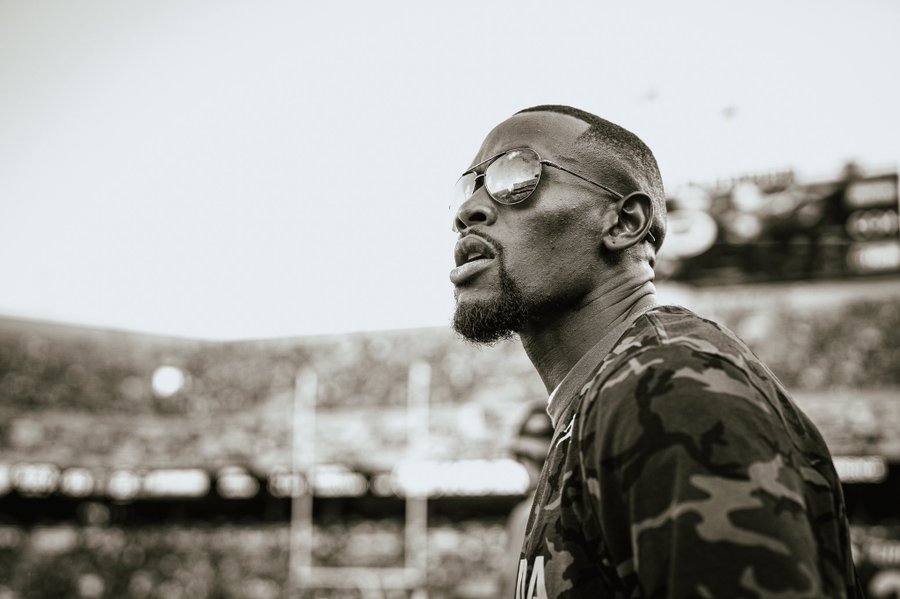

Florida coach Billy Napier wore a camouflage Louisiana hoodie Monday as he straddled his dual responsibilities as the incoming leader of the Gators and the outgoing architect of a Ragin’ Cajuns team that hosts Saturday’s Sun Belt Conference championship game.

Here are five takeaways from Napier’s Zoom media conference — his first public remarks since taking the UF job.

1. He’s focused on Louisiana…

By announcing his decision to go to UF on Sunday, Napier hoped to get that business out of the way so he could lock in on his final game at Louisiana. Coaching against Appalachian State this weekend was “non-negotiable.”

Napier said his game preparation schedule will not change this week so he can try to win his first outright conference title.

“I think from a loyalty standpoint, anything less than that would be — that’s not who we are and not what we’re about,” Napier said.

Napier said it has not yet been determined whether he’ll coach the Ragin’ Cajuns in their bowl game.

2. …but he isn’t neglecting the Gators.

Napier said he’ll devote early-morning and late-night hours “to work on some of the future challenges that we have.” Translation: recruiting and assembling a staff at UF.

He is expected to arrive in Gainesville on Sunday.

3. He sounds like Nick Saban.

Napier spent five seasons under Saban (one as an analyst, four as receivers coach) and modeled Louisiana after Saban’s Alabama dynasty.The similarities were unmistakable.

“I think the big thing here is that we don’t get too consumed with Saturday, and we focus on what we need to do each day,” Napier said. That’s coach-speak, yes, but it’s also a quick summary of Saban’s famed Process, the all-encompassing approach that stresses, well, the process, not the result.

Napier also said “you need complementary talent, but you have to have a shared vision, if that makes sense.”

It does if you understand Saban, who uses an army of analysts and support staffers to follow his top-down directives.

4. Napier explained his approach concisely.

“It’s one thing to collect talent,” he said. “I think it’s another thing to build a team. I think that’s what we’ve focused on here, is building a team.”

Both pieces are important, of course. The UF job was open (in part) because Napier’s predecessor, Dan Mullen, didn’t collect enough talent.

But the team-building aspect is key, too. Athletic director Scott Stricklin acknowledged that on the day he fired Mullen.

“You’ve got to put really good structure, culture in place in order to sustain at a high, high level over a long period of time,” Stricklin said. “That’s, going forward, what we’ve got to focus on.”

5. Napier is respected by the league.

Sun Belt commissioner Keith Gill began his portion of the Zoom session by congratulating Napier for getting the UF job. Though it’s good for the Sun Belt’s brand to have a premier program snag one of its coaches, it’s also unusual to hear a conference commissioner be so excited about a rising star leaving his league — especially at the start of a news conference about the championship game.

“(I’m) certainly excited for Coach Napier,” Gill said. “I’m probably more excited for Florida in a sense that they’re getting an unbelievable coach — unbelievable person….

“He’s one of the coaches that I certainly leaned on when I was trying to get advice and just the way he kind of approaches things, the level of care and deliberation he puts into making decisions. I was really impressed by that. Just a really smart, thoughtful, high-character person.”